| Home Page

History of B.F Skinner

Shaping Behaviour

Operant Conditioning

|

|

|

"The upshot of this scientific approach to behavioral problems is that people will become wise and good without trying, without having to be, without choosing to be. Moral training will produce men who are good practically automatically" ( Freedom and Control of Men, 1956,p.60)

Skinner's classic works were very controversial at the time. He discovered ways in which animals could be manipulated to emit behaviors which would not normally be performed. Skinner compared this learning with the way children learn to talk - they are rewarded for making a sound that is sort of like a word until in fact they can say the word.

Skinner believed other complicated tasks could be broken down in this way and taught. He even developed teaching machines so students could learn bit by bit, uncovering answers for an immediate "reward".

|

Pigeons roosted outside his office window at the University of Minnesota, which had given him the idea to use them as experimental subjects -- they became his favorite.

Pigeons roosted outside his office window at the University of Minnesota, which had given him the idea to use them as experimental subjects -- they became his favorite. |

|

What do you want to be?

Through his work in operant conditioning, reinforcement schedules, and superstition, Skinner showed parallels between animal behavior and human behavior. He felt that human behavior could be manipulated in the same manner. You don’t, for example, become a brain surgeon by stumbling into an operating theater, cutting open someone's head, successfully removing a tumor, and being rewarded with prestige and a hefty paycheck, along the lines of the rat in the Skinner box. Instead, you are gently shaped by your environment to enjoy certain things, do well in school, take a certain bio class, see a doctor movie perhaps, have a good hospital visit, enter med school, be encouraged to drift towards brain surgery as a speciality, and so on. This could be something your parents were carefully doing to you, ala a rat in a cage. But much more likely, this is something that was more or less unintentional.

|

|

Pigeons!

He found that by presenting a reinforcement every 15 seconds to a hungry pigeon in a cage, the pigeon would perform a certain ritual during the interval between reinforcements. This sort of ritual was seen six out of eight pigeons in the experiments. These superstitions, such as head bobbing, turning around, and moving toward the feeder, occurred regularly before the feeding. These behaviors had no effect on when the reinforcement was given. The reasons for these rituals were because whatever the pigeon had been doing when it was fed was reinforced. Skinner likens this to superstitions in humans. When something positive happens to us, some of the specific things associated with that positive thing are often thought to have caused it. Some professional athletes wear certain items of clothing, or jump over the baseline on their way to the pitcher's mound because they might have done these things before scoring a touchdown or throwing a no-hitter

Baby Aquariums!

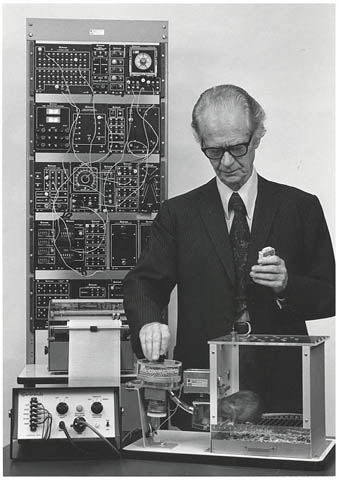

Skinner focused on following events in "frames" in order to give positive feedback at each stage of development. Immediate feedback is also essential, he said, in order to imprint the desired behavior on the learner. Skinner believed that you must "program" behavior in the learner, but also believed in self pacing of the learner. Skinner was so sure of his theories, that he implemented many of the ideas with his own children. He began development of his controversial "baby box," a controlled-environment chamber for infants .Called a "Baby Tender," he put his own children into the specially designed learning "box" in the wall of his house to stimulate their learning about the world and themselves. This special crib consisted of an enclosed space witha glass front, through which the baby could watch what was going on around her.

"The upshot of this scientific approach to behavioral problems is that people will become wise and good without trying, without having to be, without choosing to be. Moral training will produce men who are good practically automatically"

|

Rats!

Imagine a rat in a cage. This is a special cage (called, in fact, a “Skinner box”) that has a bar or pedal on one wall that, when pressed, causes a little mechanism to release a foot pellet into the cage. The rat is bouncing around the cage, doing whatever it is rats do, when he accidentally presses the bar and -- hey, presto! -- a food pellet falls into the cage! The operant is the behavior just prior to the reinforcer, which is the food pellet, of course. In no time at all, the rat is furiously peddling away at the bar, hoarding his pile of pellets in the corner of the cage. Skinner likes to tell about how he “accidentally -- i.e. operantly -- came across his various discoveries. For example, he talks about running low on food pellets in the middle of a study. Now, these were the days before “Purina rat chow” and the like, so Skinner had to make his own rat pellets, a slow and tedious task. So he decided to reduce the number of reinforcements he gave his rats for whatever behavior he was trying to condition, and, lo and behold, the rats kept up their operant behaviors, and at a stable rate, no less.

Rats!

Imagine a rat in a cage. This is a special cage (called, in fact, a “Skinner box”) that has a bar or pedal on one wall that, when pressed, causes a little mechanism to release a foot pellet into the cage. The rat is bouncing around the cage, doing whatever it is rats do, when he accidentally presses the bar and -- hey, presto! -- a food pellet falls into the cage! The operant is the behavior just prior to the reinforcer, which is the food pellet, of course. In no time at all, the rat is furiously peddling away at the bar, hoarding his pile of pellets in the corner of the cage. Skinner likes to tell about how he “accidentally -- i.e. operantly -- came across his various discoveries. For example, he talks about running low on food pellets in the middle of a study. Now, these were the days before “Purina rat chow” and the like, so Skinner had to make his own rat pellets, a slow and tedious task. So he decided to reduce the number of reinforcements he gave his rats for whatever behavior he was trying to condition, and, lo and behold, the rats kept up their operant behaviors, and at a stable rate, no less.

|

|

|

|